Spot a Scam Aimed at Students & Protect Yourself

You might have received one in your inbox recently—a suspicious-looking email from someone offering you a job on campus, claiming to be a professor or faculty member. Phishing scams are becoming more common and elaborate, and as busy students, we are often targeted and consequently fall victim to these scams.

For some, falling for these scams means losing money. One student received an email from someone pretending to be a UC Berkeley professor offering a research assistant position. Interested, the student gave their phone number when asked, and accepted the role. The student was then forwarded an online check to deposit for materials for the alleged position and was then told to forward the payment to a Zelle account before the original check was processed. They lost $1,450.

Falling for one of these scams can happen to the best of us. I recently spoke with Craig Carlson, a staff member of the Information Security Office who assists students reporting phishing incidents. He provided some insight into the types of scams students receive and how we can protect ourselves and learn to spot them. Read his advice and other practices to keep you safe along with resources on campus to help you below.

Defense Principles to Avoid Scams

The best protection against scams is not to get hooked. Some key principles to help you with this:

- Don’t make financial decisions when you’re stressed or rushed. Stop to take a breath and take a moment to think. Scammers like to rush you and create a sense of urgency—take your time to process and understand the situation.

- Don’t respond to unsolicited contact. If an organization or person contacts you, only respond through official channels.

- Don’t answer phone calls you didn’t request—even if they are allegedly from your bank. Legitimate businesses will leave you a voicemail. If you need to return a call, use the official number (found on the website or the back of your debit card for banks).

- Don’t click on links in texts or emails that you didn’t request. Don’t log in through a text or emailed link—navigate to the official website.

Red Flags

Scammers like to target people who are busy, stressed, or distracted, which makes students particularly vulnerable. Even when vigilant or when you think “you know better,” they use tricks to lower your defenses and make you feel rushed into decision-making. Here are some red flags to watch for and things to keep in mind:

If it sounds too good to be true, there’s a good chance it’s a scam. Sometimes the signs are subtle, but if you’re ever in doubt take some of the actions listed below in the “Take Steps to Protect Yourself” section.

Never provide personal information, including an alternative email or your phone number. A UC Berkeley internship or work-study position is never going to ask you for an alternate email address. “Conducting the fraud via personal email or over text takes the scam off university channels, allowing senders the university has blocked to communicate with the campus community,” according to Craig. Don’t share things like bank account information, your Duo 2 Factor Code, or a physical mailing address.

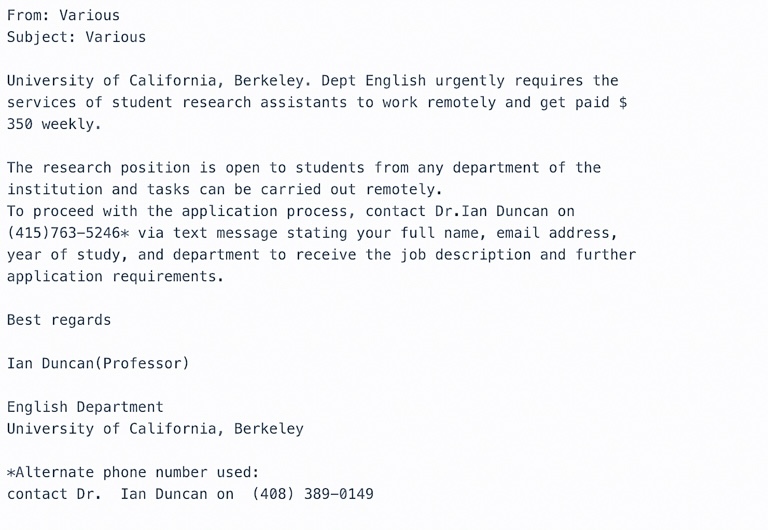

An example of an employment scam from the Phish Tank, the English Dept. (Prof. Duncan) Job Offer scam. Note how it asks you to contact Dr. Ian Duncan via a cell phone number and creates a sense of urgency.

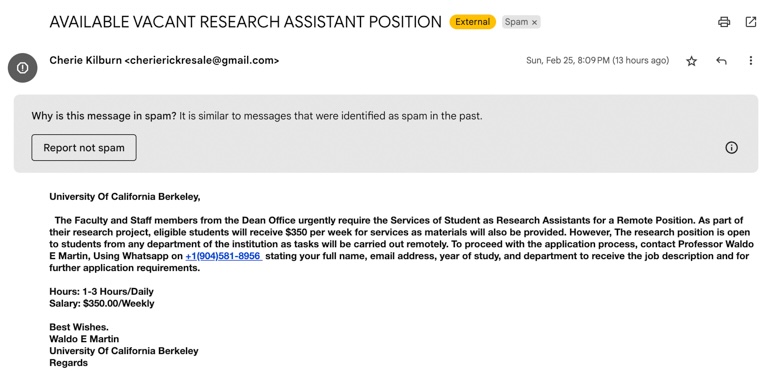

Be wary of non-Berkeley accounts. Phishing scams will almost always come from a non-berkeley.edu email account. Gmail, Wix, ProtonMail, or a stolen account from universities are the most common.

Look out for compromised berkeley.edu accounts. Even if the email comes from a berkeley.edu address, it may be compromised. Being sent a check as an attachment and then being asked to print it and deposit it is a big red flag. “These checks can look very legitimate but are completely fake,” says Craig. Checks from UC Berkeley are mailed physically or deposited directly into your account.

Note spelling mistakes and grammatical errors. Typos can be found in the body of an email or text, or the name of the sender. Scammers often change or add a single letter to spoof an address or URL.

Be careful with messages that create urgency. While many legitimate senders will highlight important deadlines. The usage of “URGENT” or “Immediate Response Needed” is a sign to slow down and double-check what the sender is providing or requesting.

A phishing email I received recently. It went straight to my spam folder because it was flagged as an email outside of my organization (berkeley.edu). Note how it asks to communicate with you on WhatsApp, and the odd grammar mistakes sprinkled throughout.

Watch for repeat scam attempts on a new platform. If you’ve been targeted once, you could be targeted again. The second attempt might even have some sort of “fraud prevention” angle.

Common Types of Scams

The single most popular scam that is sent to students is the “fake internship’” scam, or “employment scam.” These will often be presented as a well-known campus professor offering remote work—like the English Dept. (Prof. Duncan) Job Offer scam linked above.

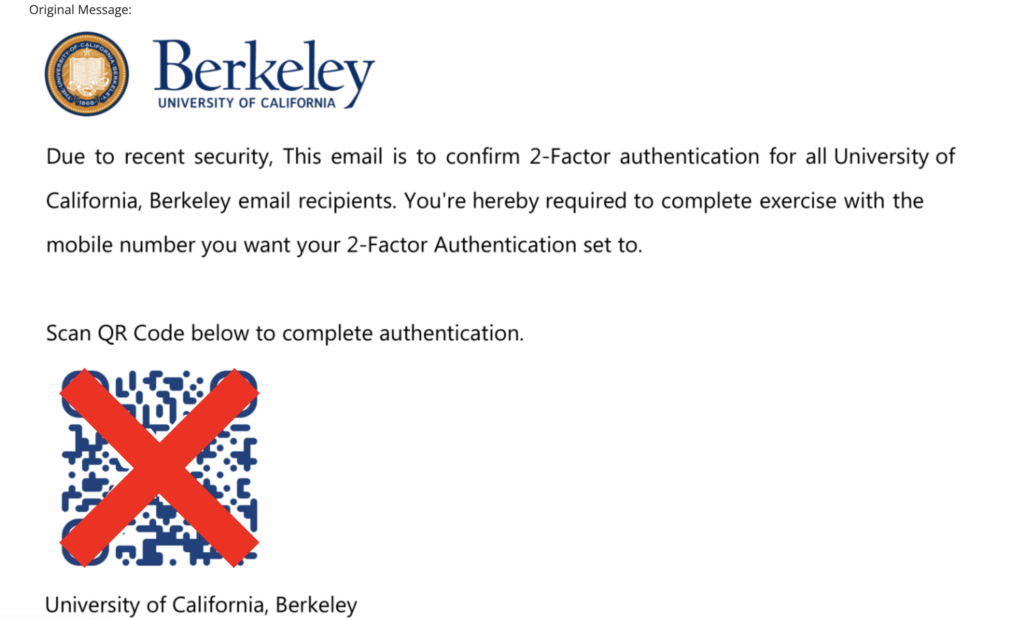

Two other common scams are the “Fake DUO Authentication Requests” and “Campus Email Account Suspension.” Both are hoaxes designed to steal account credentials, which are then used to send more phishing emails.

Example of a Fake Duo Authentication Request scam from the Phish Tank. Note the odd capitalization and grammar.

“There have also been some newer ones on the rise, where students are presented with false work opportunities with UNICEF or the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, or a parent of a student is contacted to pay for damaged lab equipment,” says Craig.

The Information Security Office has a “Phish Tank,” a collection of examples of phishing emails received on campus designed to help educate students on what a phishing email can look like and how to spot one.

Take Steps to Protect Yourself

If you receive a suspicious email, report it. Follow these steps, as outlined by the Berkeley Information Security Office:

- Open the message.

- To the right of the ‘Reply’ arrow, select ‘More’ (typically denoted with three vertical dots).

- Then click ‘Report phishing.’

Contact campus IT or Security. If you suspect you’ve received one of these scam emails or are communicating with a scammer, forward the email to phishing@berkeley.edu. If there’s any hint that a message just doesn’t seem right, or any requests for information or demands are made within an email, even if it sounds like it comes from an authoritative UC Berkeley professor, don’t hesitate to contact phishing@berkeley.edu or the Information Security Office security@berkeley.edu. They respond within the same day, usually within four hours.

Consider reducing your online profile. If your email address is public, on the UC Berkeley website directory, or other platforms, consider not including it to reduce your chances of being emailed. Also, be very conscious of what personal information you post on social media and other online platforms—things like your personal cell phone number and email address.

Do your own investigating. Sometimes you can identify the scam on your own. Here are some ways to do that:

- An internet search may easily reveal fraud—google the phone number or message being sent to you and see what comes up.

- Check with friends—did they receive something similar to their berkeley.edu emails?

- Float over URLs and addresses to help you decide if a link might be harmful, and to learn its final destination.

Ask for help if you think you’re dealing with a phishing scam.

What to Do If It Happens to You

Notify IT. “If you have already begun a conversation and started interacting with the fraudster, it is never too late to stop and reach out to our office,” says Craig. If you’re unsure about the next steps, contact the Information Security Office.

Submit a police report. If the scam has developed and you have lost money, submit a UCPD Police Report and notify your bank immediately. If the money was transferred via an online payment service like PayPal or Zelle, contact the service and report the fraud. “Even if you have not lost money,” says Craig, “we encourage students to report it because it records the attempted fraud and can help us prevent it in the future.”

Be gentle with yourself and seek help if you need it. There are a lot of real and legitimate emotions that can arise if you’ve been the victim of a scam. If you want to talk to someone about the experience, the university has counseling services, like Let’s Talk sessions, free and confidential talks with a counselor.

Resources

In addition to the “Phish Tank,” the Information Security Office has a lot of other helpful phishing-related resources, including:

- “Fight the Phish,” an awareness campaign with materials to help you identify, report, and avoid these types of scams.

- Phishing Awareness Videos, covering many similar topics but in video format.

- Cybersecurity in a Nutshell is a helpful guide to protecting yourself online.

- Berkeley Career Engagement has a guide for researching employers safely

- UCPD’s Avoiding Scams Page lists other types of scams students may encounter.

- Berkeley International Office’s Scams and Safety Page lists tips to keep yourself safe and common scams.

Not all student experiences with these types of scams end badly. One student reached out to the Information Security office, wondering whether or not their interaction was a scam. They had been offered a part-time research assistant job and were even asked for their resume. The student was then sent a $1,100 check to deposit—but the check was unable to be deposited. The Information Security Office was able to help with the next steps, including identifying the scam for what it was.

Learning to recognize these types of scams is the first and most important step in protecting yourself against them. And remember, if you see something, say something. In this case, it’s as simple as forwarding the email to phishing@berkeley.edu!

Melissa Mora-Gonzalez is a third-year at UC Berkeley majoring in English and minoring in conservation and resource studies.

Want More?

- Discover free tech resources at Cal

- Learn about wellness resources offered on campus

- Stay safe and enjoy the nightlife in Berkeley